Imagine a bustling city, its inhabitants engaged in a myriad of activities, each contributing to the intricate network of urban life. Now picture a small village, where generations have lived side-by-side, bonded by shared customs, traditions, and a deep sense of belonging. These contrasting scenarios exemplify two fundamental types of social cohesion: organic and mechanical solidarity, concepts first articulated by the influential French sociologist Émile Durkheim. What sets these social bonds apart, and how do they influence the fabric of our societies? This exploration delves into the fascinating world of organic and mechanical solidarity, shedding light on the invisible forces that shape our social interactions and bind us together.

Image: www.youtube.com

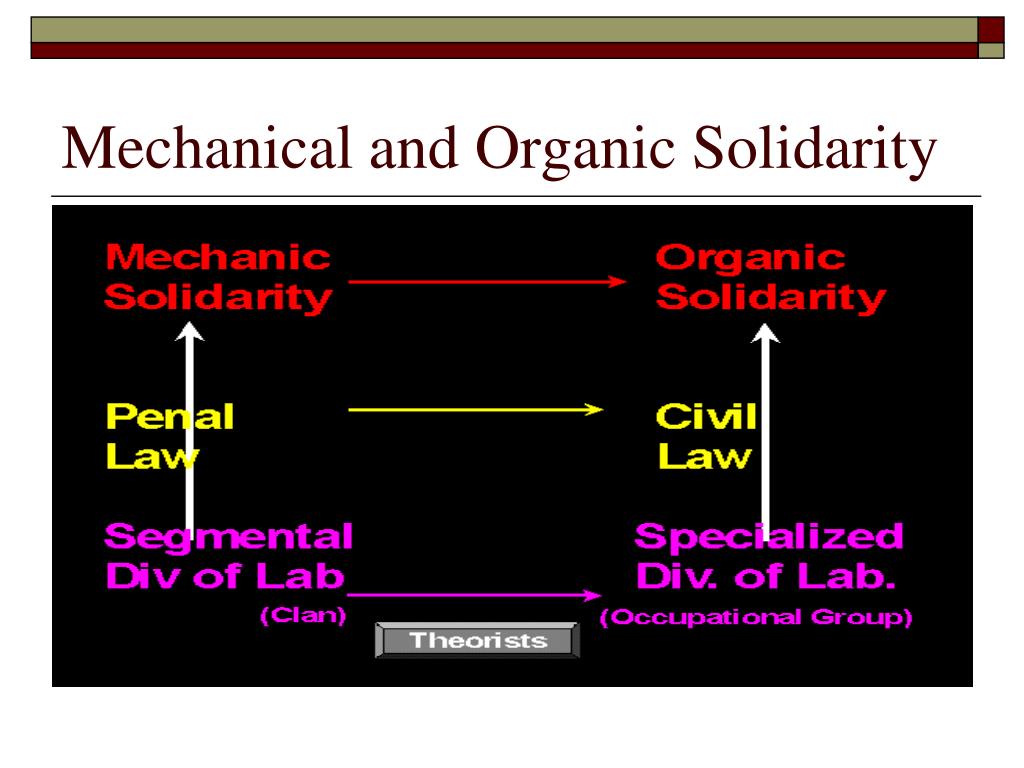

Emile Durkheim, a founding figure in the discipline of sociology, was deeply intrigued by the question of what holds societies together. In his seminal work “The Division of Labor in Society” (1893), he introduced the concept of social solidarity, a shared sense of belonging and collective commitment that binds individuals within a social group. Durkheim proposed that there are two primary forms of social solidarity: mechanical solidarity, which predominates in simpler societies, and organic solidarity, characteristic of more complex, modern societies. These two types of solidarity reflect the social fabric, depicting the mechanisms of integration and shared values that govern the interconnectedness of individuals within a society.

Mechanical Solidarity: The Tapestry of Tradition and Shared Beliefs

Imagine a small, close-knit community living in a rural setting. Their lives revolve around shared customs, traditions, and a strong belief in the collective good. This is a picture of mechanical solidarity, where individuals are bound together by a collective conscience, a shared set of beliefs, values, and norms. In simpler societies marked by homogeneity and a strong sense of communal identity, mechanical solidarity thrives. The collective conscience acts as an invisible force that dictates social behavior, ensuring conformity and unity.

Features of Mechanical Solidarity:

- Strong Collective Conscience: Individuals in such societies share a strong sense of belonging and a clear understanding of what is expected of them. This collective conscience acts as the moral compass, guiding social behavior and ensuring conformity.

- Limited Division of Labor: Individuals often perform similar tasks, contributing to the collective good. This homogeneity breeds a sense of shared purpose and reinforces social bonds.

- Repressive Law: Punishments for deviance are typically harsh, focused on enforcing conformity and preserving the collective conscience. This reflects the strong moral imperative to uphold tradition and shared values.

- High Social Cohesion: The shared beliefs and values reinforce a strong sense of community and interdependence. The collective conscience acts as the glue that binds individuals together, fostering a high level of social cohesion.

- Example: Think of small, isolated tribes or traditional villages where everyone knows everyone else, and social life revolves around shared customs, rituals, and beliefs. The collective conscience exerts a strong influence, shaping the daily lives and ensuring a sense of belonging within the community.

Organic Solidarity: The Interdependence of Specialization

As societies evolve and become more complex, the division of labor becomes a significant factor in shaping social life. Individuals specialize in specific tasks, contributing to a larger collective effort. This shift from homogeneity to heterogeneity marks the emergence of organic solidarity, characterized by interdependence and a sense of mutual responsibility. In this type of solidarity, individuals are bound together not by shared beliefs but by functional necessity, relying on each other’s specialized skills and contributions to maintain social harmony.

Image: www.slideserve.com

Features of Organic Solidarity:

- Weak Collective Conscience: The specialization and heterogeneity inherent in modern societies lead to a weakening of the collective conscience. Individuals may hold diverse views and values, leading to a greater degree of individual autonomy and a more complex moral landscape.

- Extensive Division of Labor: Complex societies thrive on a vast network of specialized skills and professions, leading to a highly interdependent society. Each individual, by virtue of their specialized contribution, plays a crucial role in the functioning of the society.

- Restitutive Law: The focus shifts towards restoring order and compensating for harm rather than emphasizing punishment. Laws are more complex and nuanced, reflecting the diverse needs of a specialized society.

- High Interdependence: Individuals rely on one another more than ever before. Their diverse skills and contributions create a network of reciprocal dependence that underpins the smooth functioning of the society.

- Example: Consider a modern city where individuals fulfill diverse roles, from doctors and engineers to teachers and artists. The city functions as a complex ecosystem, with each individual contributing their unique skills to the overall well-being of the society.

The Transition from Mechanical to Organic Solidarity: A Journey of Social Evolution

Societies rarely experience a complete shift from one form of solidarity to the other. Instead, the transition from mechanical to organic solidarity is a gradual process driven by social changes. As societies evolve, the division of labor becomes more complex, leading to increased specialization and a weakening of the collective conscience. This process is often fueled by technological advancements, economic growth, and cultural shifts.

Key Factors Influencing the Transition:

- Technological Advancements: New technologies create new industries and professions, requiring specialized skills and knowledge. This leads to a greater division of labor and a shift towards organic solidarity.

- Economic Growth: As societies develop economically, they become more complex, with increasing specialization and interdependence. This economic growth fosters the conditions necessary for the emergence of organic solidarity.

- Urbanization: As populations move to cities, social interaction becomes more impersonal, and the bonds of traditional communities weaken. The increase in diversity and cultural heterogeneity contributes to a shift towards organic solidarity.

- Cultural Change: Changes in cultural values and norms, often driven by technological advancements and economic shifts, contribute to the weakening of the collective conscience and the emergence of organic solidarity.

The Challenges of Organic Solidarity: Individualism and Social Fragmentation

While organic solidarity offers the benefits of greater efficiency and a broader array of skills, it also presents potential challenges. The weakening of the collective conscience can lead to a sense of individualism, potentially causing social fragmentation and a decline in shared values. Without a strong collective conscience to guide social behavior, moral ambiguity and cultural clashes can arise, leading to social unrest and a breakdown of social order.

Potential Problems:

- Loss of Shared Values: As societies become more diverse and individualized, shared values and beliefs may weaken, leading to a sense of moral relativism and potential social disharmony.

- Social Fragmentation: The emphasis on specialization and individual autonomy can foster a sense of isolation and fragmentation, weakening social bonds and community spirit.

- Anomie: A state of normlessness where individuals lack clear guidelines for behavior, can result from the decline of the collective conscience. This can lead to increased crime, deviance, and a sense of societal instability.

Finding Balance: Fostering Solidarity in a Complex World

The challenges posed by organic solidarity necessitate a conscious effort to promote social cohesion and cultivate a sense of shared purpose. This requires a commitment to fostering civic engagement, promoting social justice, and creating inclusive spaces where individuals can connect and build relationships.

Strategies for Building Solidarity:

- Strengthening Civil Society: Encouraging citizen participation in community organizations, charities, and social movements can foster a sense of shared responsibility and belonging. Civic engagement helps bridge social divides and promotes collective action.

- Promoting Social Justice: Addressing inequalities and fostering social mobility can enhance social solidarity by ensuring that everyone has access to opportunities and resources. It creates a sense of fairness and reduces social tensions.

- Nurturing Intercultural Understanding: Encouraging dialogue and exchange across cultural boundaries can promote tolerance, empathy, and a sense of shared humanity. This fosters social cohesion by reducing biases and prejudices.

- Promoting Education and Lifelong Learning: Providing access to quality education empowers individuals to contribute meaningfully to society. It cultivates critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and a sense of shared responsibility.

Organic And Mechanical Solidarity

Conclusion: The Importance of Understanding Social Solidarity

Understanding the concepts of organic and mechanical solidarity offers valuable insights into the forces that shape our societies. By recognizing the ways in which social bonds evolve over time, we can better appreciate the challenges and opportunities facing modern societies. It’s crucial to acknowledge the potential for social fragmentation and the need to foster social cohesion, even as we celebrate the diversity and complexity of the modern world. By promoting shared values, ensuring social justice, and fostering meaningful connections, we can navigate the complexities of organic solidarity and build a more equitable and harmonious society.

/GettyImages-173599369-58ad68f83df78c345b829dfc.jpg?w=740&resize=740,414&ssl=1)